Economics 2023: First Prize

Government spending on hospitals, school, roads and the rest is funded from taxation or government borrowing. Both are constrained. Raising government debt to very high levels risks a sovereign debt default, which would likely lead to a near-immediate collapse of consumer confidence and capital flight, culminating in an economic meltdown.Meanwhile, taxation saps purchasing power from consumers and directly reduces material welfare.Could there be a better way to finance government spending? Why can’t governments just print more money to do so?

This essay argues that financing fiscal expenditure solely by creating of money (most of which is electronic rather than printed) is economically infeasible because it risks hyperinflation and worsening income inequality. However, partial financing of government spending from newly created money does have its uses in times of cyclical economic downturns, provided the CB maintains its independence and money creation is regulated within a strong legal and operational framework.

Think of “printing money”, and the hyperinflation of Zimbabwe and Weimar Germany come to mind. Fisher's Quantity Theory of Money implies that money supply and the average price level of an economy varies with the money supply (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Fisher’s Equation

In the long run, with the economy operating at full employment, T remains constant, while V is assumed to be constant for a given economy. Thus, increasing money supply inevitably engenders inflation.

The biggest cost of inflation is the erosion of purchasing power, which reduces real consumer income, and hence the material standard of living.Should the central bank fail to maintain price stability, public trust in economic institutions maybe lost, destabilising the economy.

Both factors aggravate each other in an inflationary spiral, whereby consumers increase their marginal propensity to consume due to inflationary expectations, which further increases price levels through demand-pull inflation, potentially resulting in hyperinflation.

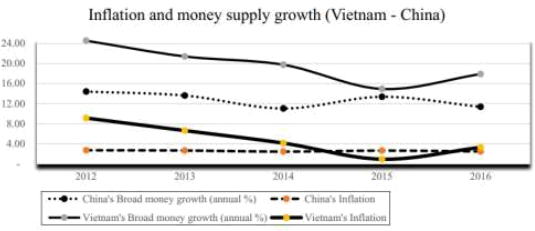

While empirical research has shown that money supply and inflation are positively correlated (Fig. 5), perhaps the consequences of excessive money printing is more clearly seen from historical events.

Fig. 2: China and Vietnam’s Inflation and money supply growth are positively correlated

Several factors contributed to the decade-long hyperinflation crisis in Zimbabwe. These include excessive money printing to finance military intervention, followed by 5 billion dollars’ worth of pensions for veterans.Monthly inflation in Zimbabwe peaked at 79.6 billion percent in November 2008.Citizens suffered a near-complete erosion of their real incomes. Confidence in the government and currency was lost. Similarly, when the Weimar Republic resorted to printing money to repay Allied reparations in 1922, the resultant hyperinflation led to a breakdown of law and order.If financing most government spending by printing money causes hyperinflation, financing all government spending by printing money surely would too.

Of course, money printing may not necessarily result in inflation under certain circumstances. Firstly, with an severe lack of demand from the private sector, it is unlikely that inflation would be severe. Despite expanding the money supply in 2013 and Yield Curve Control in 2016, Japan has struggled against deflation for decades due to relatively stable inflationary expectations and weak private sector demand, caused by a falling population and a high marginal propensity to save.Furthermore, should the central bank credit newly created funds to private banks, the extent of inflation depends on private banks’ willingness to lend. In the aftermath of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, banks’ tendency to keep the Federal Reserve’snewly created money as reserves meant that inflation was hardly affected, as the ratio of commercial bank money to reserve bank money shrank.Despite this, these circumstances are highly specific and in the case where printing money is the sole method of funding the fiscal expenditure, the extent of printing money is so great that inflation is guaranteed.

Constantly increasing the money supply would also inevitably lead to a long-run depreciation of the currency in the foreign exchange market.This poses two risks. First, the existing inflation -caused cost of living crisis is further exacerbated by imported inflation, especially if the economy is relatively import-reliant with a current account deficit.Both imported consumer goods and factors of production become more expensive in domestic currency terms. Second, a prolonged devaluation of the currency would have negative implications on international trade relations, negatively affecting the economies of trade partners via a beggar-thy-neighbour effect. Should these trade partners choose to take up retaliatory action, the economy’s export revenue, economic growth and employment would suffer. China, labelled a currency manipulator by the US for artificially deflating its currency, has suffered a significant decrease in economic activity after the imposition of US tariffs. The hardest hit 2.5% of the population experienced a 2.52% contraction in GDP and 1.62% reduction in manufacturing unemployment relative to those unaffected.

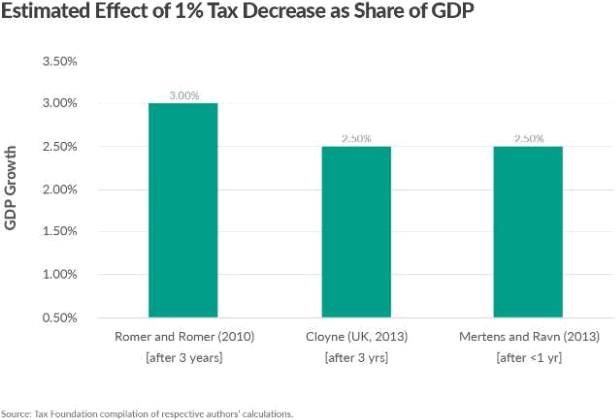

Proponents of printing money to fund government spending may argue that the elimination of taxation would increase economic growth. Empirical research (Fig. 3) has shown that by decreasing income taxes, consumers’ disposable income, purchasing power, and thus private consumption would be significantly higher. The absence of corporate taxes would similarly lead to increased private investment due to increased post-tax profits.With increases in government spending no longer requiring tax hikes, consumer confidence would increase significantly, further increasing private sector spending. Given that private consumption and investment are key contributors to aggregate demand (AD = C + G + I + X − M), the resultant increase in aggregate demand would lead to a multiple increase in real GDP, facilitated by the Keynesian multiplier effect (Fig 3.).

Fig. 3: GDP growth from reduced taxes

Despite this, when it comes to printing money there are serious concerns about worsening income inequality. Firstly, while taxes may hinder purchasing power, they are a crucial wealth redistributor. Without them, existing income inequality would be exacerbated. Studies have shown that a more progressive tax structure is related to higher levels of well-being. Even if the government were to attempt to resolve this issue through direct transfer payments to the poor to raise their material wealth using its now unlimited funds, such a policy would unlikely be effective, given the high likelihood of inflation which would negate any increase in purchasing power and economic growth.

Furthermore, money creation disproportionately benefits the wealthy. Studies have shown that rapid money creation has contributed to speculative activity and bubbles in the stock market,likely due to the lowered interest rates and greater confidence encouraging investment into riskier equity markets. This disproportionately benefits largely well-off stock owners, while the less wealthy lose out.

The greatest benefit of relying solely on MF would be the increased flexibility in implementing fiscal policy, especially crucial during periods of economic downturns.

Money printing provides policymakers with a tool to stimulate aggregate demand when the economy needs it most, by financing fiscal stimuli. Fiscal stimuli are essential to minimising the impacts of an economy-wide recession as they boost economic activity more quickly and sometimes more effectively than other alternatives, reducing the length and severity of recessions.MF also allows the government to circumvent the commonly faced limitations of conventional monetary policy during a recession, which may include the zero lower bound of interest rates and the risk of a liquidity trap.The government effectively removes any budgetary ceiling to government spending, allowing it to mitigate the impact of recessions with ease.

Conventional policies are considerably less risky during normal times. However, there still may be a place for MF as a last-resort in times of cyclical downturns, when conventional economic policies have shown to be ineffective. However, it is imperative for central banks to be aware of the immense risks to avoid a potential economic catastrophe.

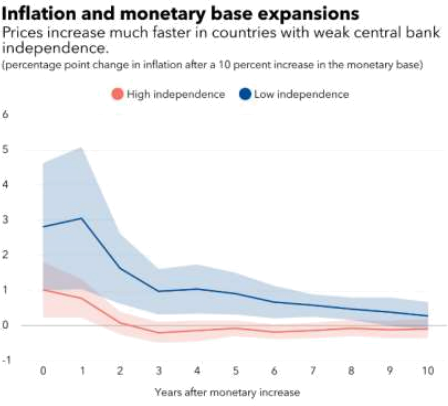

First, the central bank must remain an independent and credible economic institution, because this promotes price stability.

Fig 4: Inflation is higher in economies with lower CB independence

In the case where inflation begins to get out of hand, the central bank should not hesitate to reduce or stop financing government spending. Failure to do so would cause a significant loss in confidence in the central bank’s ability to stabilise prices, leading to a hyperinflation. Furthermore, there should be checks and balances that ensure legislators do not abuse the central banks money-creation powers to fund irresponsible government spending. One example is imposing a hard limit on the amount of funds that the central can create. Such checks and balances would enable the central bank to remain an effective regulator of price levels.

There should be clear guidelines on money creation within a strong operational and legal framework: strict activation clauses, a clearly-defined scope, timeline and exit strategy. The goal of such a policy should be achieving economic stability rather than financing irresponsible government spending, and should be decided by an independent and reputable central bank.

In all, total reliance on printing money to fund fiscal expenditure is unlikely to be feasible, given the aforementioned risks to price stability, international trade relations, and income equality. However, it can be a useful tool to a stimulate demand during cyclical downturns, and in other exceptional situations where conventional policies have been exhausted.